On October 24, 2021, Rory Kramer, PhD and Brianna Remster, PhD of Villanova University submitted written testimony to the Michigan Independent Citizen’s Redistricting Commission (MICRC) advocating against prison gerrymandering in Michigan. VAAC is very grateful to these scientists for their efforts on behalf of fair maps in Michigan.

As social scientists, Kramer and Remster created a model for estimating the impact of prison gerrymandering on legislative representation. This model was vigorously peer reviewed and published in a leading social science journal (Remster and Kramer 2018).

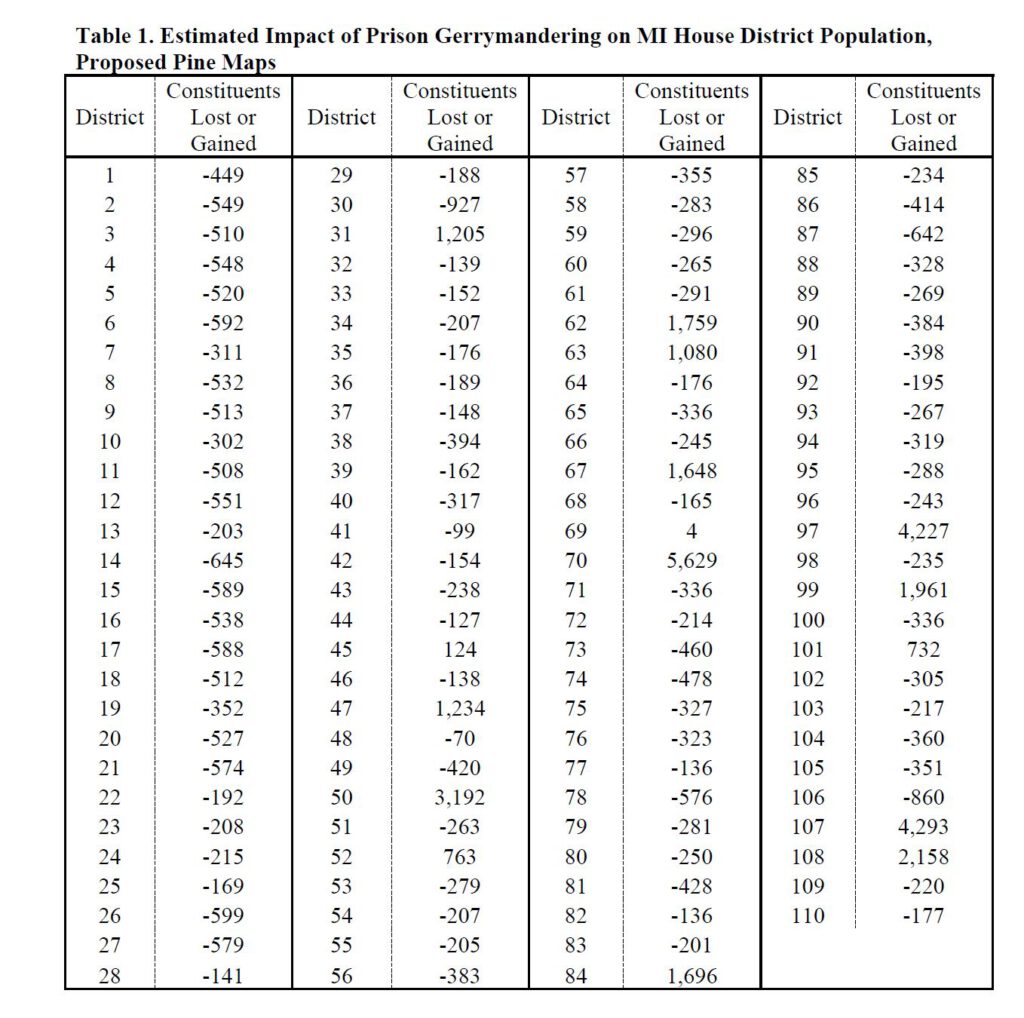

Kramer and Remster applied their model to two of the MICRC draft maps and presented the following findings to the commission. To read the full report, click here.

- Unlike other states we have analyzed, because Michigan’s Commission did not pack people of color into urban districts, none of the districts grew large enough after our analyses to become legally too large. However, we are concerned that State House Districts 9 and 73 grow close to that cut off, within 1000 residents of the maximum size, using our conservative estimation strategy. District 9 is majority Black and District 73 has more residents of color than the state as a whole (34% compared to roughly 25%).

- On the other hand, proposed House Districts 107 and 70 have such a large portion of their population incarcerated that they would be constitutionally too small were Michigan to reallocate incarcerated individuals to their home communities. Both 107 and 70 would be more than 1500 residents short of the district size cut-off if it weren’t for incarcerated persons. Moreover, these two proposed districts are disproportionately non-Hispanic white whereas incarcerated Michiganians are disproportionately Black and Latinx.

- These impacts are not a simple urban/rural divide. Most rural districts do not contain prisons—only 15 House Districts and 10 Senate Districts have state prison facilities of any size—which means that most rural residents’ representation is negatively affected by counting incarcerated people where they are confined. In fact, most Michigan residents have less representation because of this policy whereas a small portion have more representation simply because they live near a prison.

- Figure 1 shows that counting incarcerated people in correctional facilities boosts white representation across the board. Although only districts with prisons benefit, the average white Michigander lives in a house district that has 56 more residents than it would without prison gerrymandering. For senate districts, the average white resident has 30 more people.

- Counting incarcerated people in correctional facilities harms Black representation in Michigan (see Figure 1). The average Black Michigander lives in a house district that has 316 fewer residents because of prison gerrymandering. Their senate district also has on average 712 fewer residents. Because incarcerated individuals, their families, friends, even their crime victims, typically congregate in the same neighborhood, legislators representing Black communities often have more constituents requesting support services compared to legislators representing white communities, especially those with a prison in their district. This policy punishes every single resident of a district that is heavily policed, regardless of whether they have ever been incarcerated. Combined with residential segregation, Black Michigan residents have less representation than white residents because of where incarcerated people are counted.

Leave a Reply