A fantastic story about VAAC’s work was published in the Detroit Free Press on September 28th, 2022. There is also a video accompanying the article. Click this link if you have a subscription, or read the story below.

We are so proud of the VAAC members mentioned in the article and interviewed in the video. They are truly making a difference!

In Michigan, many in jail face gap between right to vote and opportunity to exercise it

For Tia Gaines, filling out an absentee ballot was a way to reconnect with the community outside the walls of the Genesee County Jail.

“It makes me feel like I’m still a part of society, like my vote still matters,” Gaines said moments before heading behind the voting booth set up for her and others incarcerated in the Flint jail to cast their votes for the recent August primary. One said she was voting for the first time.

“Even though they’re in here, they want to make sure once they return to the community, they have played a part in who’s an elected official that represents them,” said Percy Glover, a Genesee County deputy sheriff ambassador who has helped spearhead the voting program at the Flint jail.

But many eligible voters in Michigan’s jails don’t know they have the right to vote or lack the assistance they need from county sheriffs to participate in elections, according to advocates seeking to expand jail voting in the state.

Under Michigan election law, only those serving out a sentence are excluded from voting if they’re otherwise eligible to vote. Those who are not serving a sentence in jail or prison but who are still incarcerated — often because they are awaiting trial or are in the middle of one — are still eligible to vote. And those who have completed their sentence automatically have their right to vote restored upon release, including those on probation or parole.

“When you look at the big picture of jails across Michigan, you’re talking about thousands of people who are being disenfranchised because there’s not a voting process in place for them,” Glover said.

For eligible jailed voters, the ability to exercise their constitutional right to participate in elections often depends on whether their jail has programs in place to help them register to vote and cast an absentee ballot. Jails with voting programs in place are the exception, not the norm.

“It is a failure of our democracy that thousands of these eligible voters are excluded from elections every year merely because they are overlooked and under-resourced,” reads a report on the issue from Voting Access for All Coalition and Nation Outside released last year. The coalition works with jails across the state to help more eligible incarcerated voters and those formerly incarcerated participate in elections.

In making the case that Michigan jails should remove barriers to the ballot box, advocates point to studies that suggest greater participation in elections among those involved with the criminal legal system could lower recidivism. One indicates that states that bar ex-felons from voting see higher repeat offense rates.

“The more connected you are to your community, the more you feel that your voice is valued, the more that you feel that you have a positive impact, the less likely you are to commit any criminal behavior or negative behavior against your community because you’re tied in an intimate way,” said Amani Sawari from Spread the Vote during an event hosted by the Detroit Public Library on the topic.

“By registering people to vote, by having town halls where candidates come in and talk to registered voters, it allows them to see the value that they have and perhaps make a different decision that would keep them from ever coming back,” said Genesee County Sheriff Christopher Swanson.

Michigan is one of 21 states where people incarcerated for felony offenses lose their right to vote while serving their sentences but have it automatically restored upon release, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Most states further restrict the voting rights of people convicted of felonies or strip them away entirely, even after they have completed their sentence.

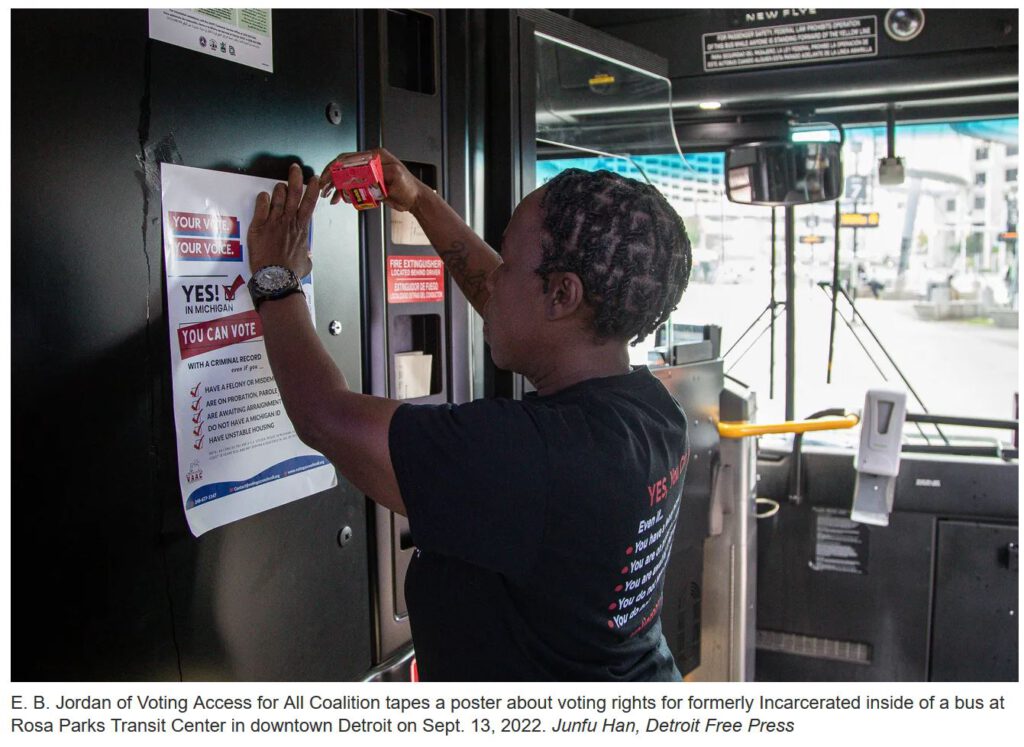

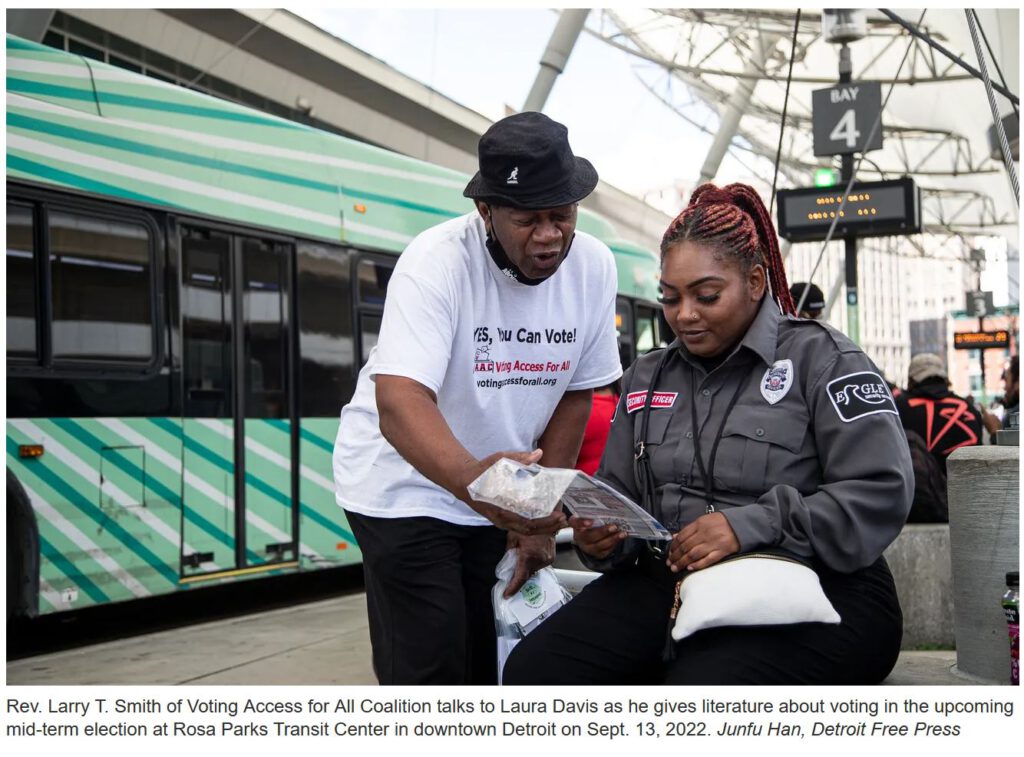

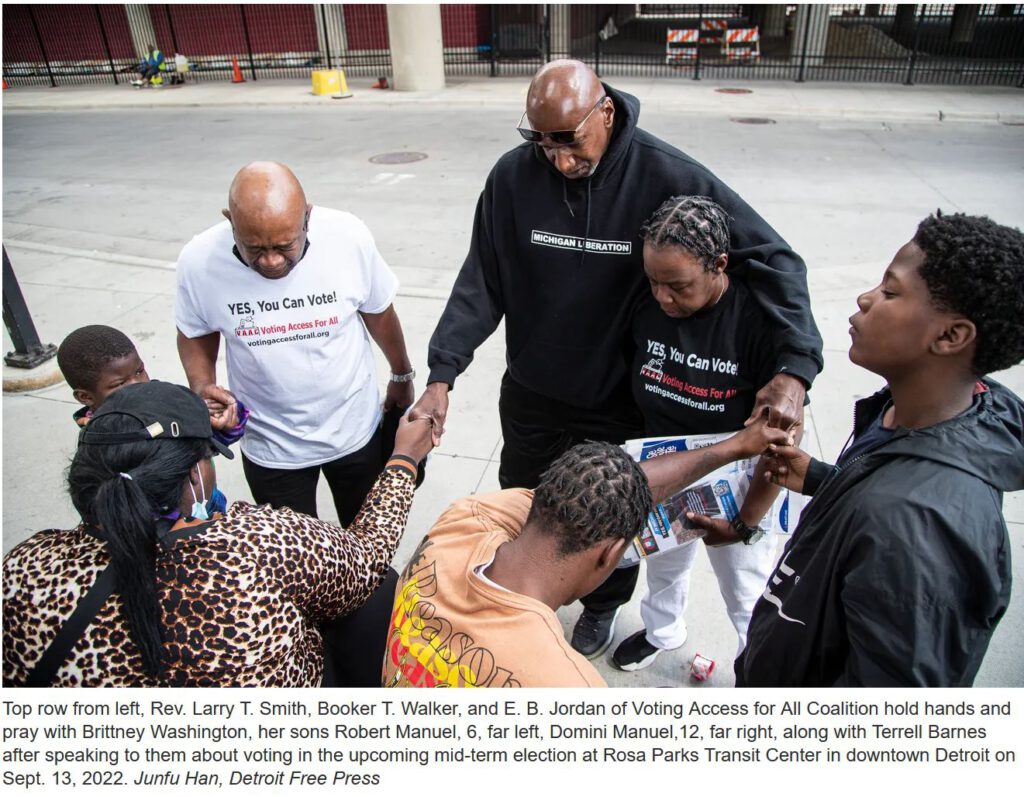

E.B. Jordan, Voting Access for All Coalition’s outreach coordinator, says many formerly incarcerated individuals she encounters are surprised to learn they have the right to vote in Michigan.

“They hit me with, ‘You mean to tell me I could have been voting all this time since I’ve been out?’” Jordan said earlier this month as she walked around the Rosa Parks Transit Center in downtown Detroit to get people waiting for their bus registered to vote.

Some sheriffs have taken steps to help eligible incarcerated individuals vote. Others have done little to provide assistance to help those eligible vote, according to the Voting Access for All Coalition and Nation Outside report.

The result is a patchwork system.

In Genesee County, Glover was deputized by the Flint city clerk’s office to deliver and return absentee ballots to and from the jail. In Ingham and Washtenaw counties, teams from the clerk’s offices visit the jails to register voters and help them request absentee ballots, according to the report. In Wayne County, a spokesperson for the sheriff’s office said earlier this month that local clerks in the county are encouraged to help eligible incarcerated voters participate in the upcoming election and that the Chief of Jails has discussed bringing in local officials to help register those eligible ahead of the upcoming November election.

In some jails, meanwhile, it can be difficult just to access the forms needed to register to vote and request an absentee ballot.

“They don’t want that extra paperwork,” Jordan said of some jail officials. “But the way I see it is you give us the towels and the sheets and the blankets for our beds, why don’t you throw some paper along with it?”

Those in jail often lack access to the internet, making them dependent on assistance from jail staff to provide and mail voting forms.

Other barriers include confusion about when and how involvement with the criminal legal system impacts the right to vote and a lack of familiarity with the candidates and proposals on the ballot, according to advocates.

Daniel Jones, the chairperson for the Voting Access for All Coalition, said candidate forums like the ones hosted in the Genesee County Jail before the recent primary can help inspire more jailed voters to participate in elections. “I think that in itself that is incentive for people to be able to vote once they are aware of who’s running for these positions and what their positions are,” said Jones.

Some options for registering to vote and casting a ballot aren’t available for those in confinement, creating another hurdle.

While same-day registration allows eligible individuals to register to vote on Election Day, those in confinement must submit their registration form at least two weeks before an election. After that, those wishing to register must do so in person at their local clerk’s office, an option unavailable to those in jail, who also can’t return absentee ballots via drop boxes, request an absentee ballot in person at their clerk’s office or vote in person on Election Day. All of that means incarcerated people who want to vote must do a lot of advance planning if their jail has not set up an official voting location.

“With the exception of a few counties, those in jail do not have access to assistance, and often find the system too difficult to negotiate alone,” the Voting Access for All Coalition and Nation Outside report states.

Advocates have pushed for legislation establishing requirements to increase ballot access for jailed voters such as legislation mandating polling locations in jails in large cities or allowing jailed voters to request an emergency absentee ballot.

Charles Thomas, a volunteer with the Voting Access for All Coalition, said incarcerated voters would be better served by a set of standard procedures to help them exercise their voting rights. “The problem is that doesn’t exist.”

Clara Hendrickson fact-checks Michigan issues and politics as a corps member with Report for America, an initiative of The GroundTruth Project. Make a tax-deductible contribution to support her work at bit.ly/freepRFA. Contact her at chendrickson@freepress.com or 313-296-5743. Follow her on Twitter @clarajanehen

Leave a Reply