This article was originally published by Prison Policy Initiative as “High stakes mistakes: How courts respond to “failure to appear”,” authored by Brian Nam-Sonenstein

People miss court for many reasons outside of their control. They can’t miss work, they don’t have childcare, or they don’t understand court instructions. Yet they are routinely seen through the eyes of the law and the media as fugitives from justice who threaten our communities, and met with unduly harsh punishments.

A cascade of negative consequences befalls those who “fail to appear”: arrest warrants, additional charges, jail and prison sentences, fines and fees, and more. None of these make it any easier to attend court, but they do heap misery and instability on the poorest and most marginalized people in the system.

Building off our previous work examining the role of “failure to appear” in bail processes and advocating for the reduced use of bench warrants, this briefing compiles research on who tends to miss court, why they miss court, and how different jurisdictions react. We also look at how people are organizing to increase court attendance, reduce harm, and importantly, question whether so many of these cases should exist in the first place.

States have a wide range of responses to “failure to appear”

Most jurisdictions provide some wiggle room for those who miss court to defend themselves, but protections are flimsy and quite limited.1 When coupled with a range of severe and counterproductive consequences, court responses to “failure to appear” (FTA) may actually make our communities less safe.

We categorized provisions within 83 laws across the states and Washington, D.C. with help from the National Conference of State Legislature’s Statutory Responses to Failure to Appear database. We find that, on balance, “failure to appear” policies are about punishment, not improving appearance rates:

| Punishments | Accommodations |

|---|---|

| 41 states impose additional criminal penalties, including contempt of court, misdemeanors, or felony charges | 40 jurisdictions including the District of Columbia consider a person’s intentions in missing court to some degree |

| 20 jurisdictions including the District of Columbia impose jail or prison time | 23 states allow an individual to mount a defense and attempt to prove to a judge that they were not evading the court |

| 17 jurisdictions including the District of Columbia levy fines or fees | 13 states provide a grace period during which a defendant can appear in court before there are consequences |

| 4 states have strict liability, meaning that no intent is required to be criminally responsible for missed court dates | 3 states distinguish treatment based on whether or not a person has left the state |

Nearly every jurisdiction permits additional charges to be brought against someone who misses court, with the exception of 9 states: Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Montana, New Hampshire, New York, Oklahoma, and South Carolina. Roughly one-third of all jurisdictions use fines, and even more use jail time, to punish absences as well. Maine, Michigan, Mississippi, and South Dakota all treat failure to appear as a strict liability offense: no evidence of intent is required to hold defendants criminally responsible for nonappearance. Meanwhile, over two-thirds of jurisdictions make room (on paper, at least) to consider circumstances and intent behind missed court dates, and close to half allow people to defend their absences. Only about one-third of jurisdictions allow some sort of grace period for someone to return to court before facing consequences.

How courts respond to nonappearances can have serious consequences for a defendant’s current and future involvement in the criminal legal system. Failure to appear weighs heavily against defendants in many pretrial risk assessment tools, used to help determine whether someone should be released pending trial. A missed court appearance could tip one’s score in favor of pretrial detention, which could last for months if not years on end. Or it can lead to suffocating conditions of release, such as electronic monitoring or frequent check-ins with pretrial officers.

The influence of missed court dates on risk scores has direct consequences for poorer defendants, who are more likely to miss court because they lack childcare or transportation, or can’t take time off from work. And because these tools compute risk scores based on a person’s demographic characteristics and record (e.g., past missed court dates, the charges they are facing, age, etc.) rather than an assessment of their circumstances (employment and housing status, health considerations, etc.), they only reinforce the underlying issues that cause missed court appearances in the first place.

Even in places that don’t use risk assessment tools, a judge’s contempt for someone who misses court can weigh heavily against a defendant’s interests to remain in the community, and in favor of pretrial detention instead. Typically, from a judge’s perspective, missed court dates give the impression that a defendant does not take their case seriously, and absences lead to further delays and inefficiencies — a major concern for overburdened courts with large caseloads.

Most people are not evading justice and don’t threaten public safety

Opposition to bail reform is primarily led by the commercial bail bond industry, which profits off of the money bail system responsible for so much pretrial detention. Bail bond agents don’t have the strong incentive you’d expect to ensure people make it to court: The industry exploits loopholes and lax enforcement to avoid paying forfeited bonds when clients miss court dates. What’s more important for them is ensuring there is a steady stream of people detained pretrial who are desperate enough to pay bondsmen to get out of jail in the first place. Though they like to say they are in the business of getting people out of jail, in reality bail bondsmen prey on people who are stuck in pretrial detention. Harsh punishments for failure to appear, which make pretrial detention and financial release conditions more likely in future cases, help sustain this industry.

To scare people onto their side, opponents often lean on the specter of “the criminal,” freed from jail but “defying” law enforcement by missing court and lurking in the community. But the reality is quite different: most people who miss court are facing low-level charges and are not evading court at all.2 In fact, roughly 25% of cases are eventually dismissed altogether, suggesting many of these people should never have been charged in the first place.

Most people who miss court are trying to attend but cannot. One report examining the reasons people miss court, conducted in Lake County, Illinois and published earlier this year, found that people simply have competing responsibilities, face logistical and technical challenges they cannot overcome alone, or are struggling with past experiences and emotional reactions. Many people are navigating more than one of these barriers to appearance at a time. Some examples from Lake County include:

| Life Responsibilities | Logistical or technical concerns | Past experiences and emotional reactions |

|---|---|---|

| Managing mental health diagnosis and medication compliance | Live in another county or state and either challenging public transit or none at all | Fearful or scared about process and going to jail |

| Moving a lot, securing shelter, navigating homelessness | Unreliable car and either a suspended driver’s license or no license | Nervous or scared |

| Serving as a primary caregiver | Bus segments don’t line up | Overwhelmed |

| Managing drug use and treatment responsibilities | No computer or internet to use virtual option | Court actors are unhelpful or refuse to help |

| Nightshift, newborn exhaustion, and forgetfulness | No password to Zoom or password not working | Court actors are intimidating or seem purposefully aggressive |

| Navigating custody and divorce cases | No directions for Zoom or not listed on Zoom | Confusing process, lack of information, too much information, conflicting information |

| Challenging family and relationship dynamics | Address issues for notices | Confusing navigating building or technology |

| Managing work responsibilities | Racist, ableist, stigmatizing experiences with the court | |

| COVID, sick, or hospitalized |

Even when people miss court, most return within a year. Take for example this study from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which focused on felony cases in the 75 largest urban counties in the U.S. Roughly 25% of people who were released without the involvement of a bail bond agent missed a court date. However, fewer than 8% failed to return to court within a year. Meanwhile, in July of this year, the Judicial Council of California released a report evaluating a pretrial release pilot program that began early in the COVID-19 pandemic, which sought to increase pretrial release rates and included a text message and phone call reminder service for court dates. Looking at a total of 422,151 people assessed as part of the pilot program, they noted a 6.8% decrease in failure to appear rates for people facing misdemeanor charges.3 This is consistent with other evidence showing that when people are met with support, they do show up: figures from The Bail Project’s 2022 annual report show that the people they supported had a 92% court appearance rate.

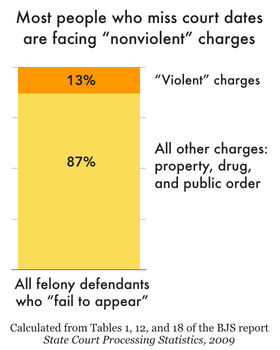

Additionally, people who tend to miss court do not pose a danger to the community. A 2013 study from the Bureau of Justice Statistics showed that people facing more serious charges missed court less often than people with lower-level offenses. Nearly 87% of people who missed court were facing property, drug, or public order charges, compared to 13% who missed court while facing charges for violent offenses.4

Missed court dates don’t make us less safe — but court responses to them do

“Failure to appear” is one of the main culprits behind an enormous backlog of warrants in the U.S. Bench warrants, issued by courts for procedural issues like missed court dates, order the police to find and arrest a person and bring them before the court. Such warrants arguably have a stronger negative impact on public safety than missed court dates themselves.

One 2018 Washington Law Review article, “Dangerous Warrants,” surfaced data from Omaha, Nebraska showing more than 40% of all outstanding warrants were for “failure to appear,” and 33% of people sought were Black in a city with a Black population of just 13%.

Meanwhile, a report from the North Carolina Court Appearance Project examining jail booking data from January 2019 to June 2021 found that “failure to appear” for misdemeanor charges was the most common reason people were jailed. Put another way, many of these people were jailed for missing court for original charges that would never have resulted in jail time. Many bench warrants are left outstanding and are never actually served, leaving the threat of arrest to linger over someone’s head in perpetuity. In this way, open bench warrants can be deeply counterproductive to the court’s stated goal of court attendance and even corrosive on public safety. While it’s uncommon for people in this situation to engage in criminal conduct, warrants help create conditions in which it may be more logical to do so. As explained in professor Lauryn P. Gouldin’s University of Chicago Law Review article, “Defining Flight Risk,” warrants create a fear of additional punishment that can dissuade someone from pursuing legitimate and stable employment for fear of being exposed on a background check. That fear might also cause someone to fail to obtain a driver’s license or apply for public benefits they need to survive. On a more personal level, it can lead to extreme stress and mental health deterioration, and cause severe strains on important relationships with friends and families. These factors can cause an inadvertently missed court date to become a persistent one, and force people to turn to crime for income and survival.

Taken together, the court’s response to an absence might itself motivate criminalized behavior, and waste law enforcement time and resources. As a result, aggressive court responses arguably pose a greater threat to community health and safety than missing court itself.

Advocates are fighting to change how we treat FTA

Fortunately, there are many people on the ground working to reduce the harm of missed court dates, interrogate the policing behind the charges, and expand pretrial release.

Injecting nuance to distinguish between evasion and understandable absences

As we discussed in our analysis above, many jurisdictions make some level of accommodations for people who miss court, whether it’s grace periods, defense provisions, or language that conditions any punitive responses on intent. This includes laws that are aimed particularly at a “willful” failure to appear, or someone who missed court “knowingly,” “without reasonable excuse,” or “intentionally.” Much of this can be attributed to organizing, such as the work of the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice and Coalition to End Money Bond in Illinois, who successfully pushed for reforms that only permit judges to detain people pretrial due to a risk of “willful flight” – not simply because they might not appear in court.

Professor Gouldin proposes a different approach involving a policy distinction between “True Flight” and “Local non-appearance.” The idea is to differentiate between someone who has left the area and someone who missed court but remains in the area and is easy to locate. She suggests the court assess absences along a matrix of persistence, cost to the court, and willfulness. Where implemented, this would represent a meaningful and commonsense improvement to court responses.

Providing services to encourage court attendance

In some places, advocates have worked to provide basic supports such as court transportation, housing, food, and health care (including substance use treatment) to people involved in the system who would struggle to attend court without them or may decide to miss court to pursue them. There are also services aimed at providing population-specific needs, such as language support and special help hotlines for immigrants who must attend court. Other advocates have worked to establish phone call and text reminder systems to alert defendants to upcoming court dates. Finally, states like North Carolina are challenging laws that impose financial penalties for missed court dates, like an end to mandatory bond doubling policies that compel judges to double someone’s bond (or secure a minimum bond for $1,000 if none was set before) for missing a court date.

Simplifying court processes

Improving communication and reducing confusion can also improve court attendance. This includes redesigning court forms and implementing flexible scheduling to reduce court wait times, identify which court dates actually require a defendant’s participation, or allow for walk-ins or easier rescheduling. It may also include better communication about court scheduling and rescheduling, since some defendants — and their attorneys — have experienced showing up to court only to find their hearing time or date had been changed.

Advocates have also argued to reduce and eliminate fines and fees, especially for people who cannot afford them, and end the reflexive issuance of bench warrants when people miss court.

Since the pandemic, some places have added the option of virtual court visits — although court systems must examine whether judges are biased in favor of people who attend in-person.

Fighting policing and charges

Perhaps most importantly, advocates are rejecting the fear mongering narrative used by bail reform opponents. They argue the emphasis on missed court dates is a distraction from the fact that so many of the charges for which people are compelled to court are eventually dismissed. According to the 2013 Bureau of Justice Statistics’ study of felony cases in large urban counties, one in four cases ended in dismissal.

Conclusion: The root of the FTA problem

If courts were truly interested in reducing absences, there are many ways they could intervene to reduce the barriers people face to attending court. Instead, jurisdictions have created laws that allow courts to ruin and incarcerate greater numbers of people before they’ve even been convicted of a crime simply for having a scheduling conflict. The accommodations we have highlighted in our analysis of state laws are good, but are not enough on their own to reduce the frequency and harm of missed court dates.

As we have said throughout this piece, harsh punishments for missed court dates inject instability into our communities, and increase the likelihood of potentially dangerous police encounters. Adding insult to injury, this approach often escalates punishments for underlying charges that, at the end of the day, would not involve jail time and are frequently dismissed.

“Failure to appear” does not threaten our safety in the way that bail reform opponents present it — what’s more pernicious is how it has traditionally been used as a backdoor to punishing people before they’ve even been convicted of a crime. In addition to stopping unnecessary policing that ensnares people in criminal legal processes in the first place, more work needs to be done to actually address obstacles to attendance and move away from harsh and punitive postures toward missed court dates.

Appendix

For details about the laws in every state that govern court responses to “failure to appear,” see the appendix table at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/fta_policies_appendix.html.

Footnotes

- Ultimately, whether a person’s “failure to appear” is excused is left to a judge’s discretion. It’s important to note, then, that our findings are based on laws and policies, and are not necessarily reflective of how those laws are or are not applied.

- Technically speaking, many “failures to appear” can be attributed to jails themselves: One in four people jailed in New York City miss court hearings and trials due to transportation delays. Last year in Los Angeles, 40% of county jail transport buses broke down, causing many people to miss court and spend more time locked up.

- The Judicial Council’s report did find a statistically significant increase in failure to appear rates of 2.5% for people facing felonies, but this may be a consequence of COVID-19-related disruptions prolonging court proceedings for people facing such charges. The longer the court proceedings, the more opportunities there are for people to miss court dates, and felony cases are typically much longer than misdemeanor cases.

- It is important to note that what constitutes a “violent crime” varies from state to state. An act that might be defined as violent in one state may be defined as nonviolent in another. Moreover, sometimes acts that are considered “violent crimes” do not involve physical harm. For example, as The Marshall Project explains, in some states entering a dwelling that is not yours, purse snatching, and the theft of drugs are considered “violent.” The Justice Policy Institute explains many of these inconsistencies, and why they matter, in its report Defining Violence.

This article was originally published by Prison Policy Initiative as “High stakes mistakes: How courts respond to “failure to appear”,” authored by Brian Nam-Sonenstein