Millions of incarcerated people face deadly and abusive conditions every day in the United States because most jailers and prison administrators have free reign over their lives. For many corrections departments, meaningful and effective oversight is the exception, not the rule. Take Oregon, for example: sheriffs inspect each other’s jails and give out perfect scores while reporting record-breaking death counts in their custody. In the state’s prisons, officials have failed to keep track of complaints against corrections staffers and flout requests for information about how often incarcerated people are locked down or experience overdoses.

Courts are basically the only oversight most jails and prisons have–an arrangement that leading oversight scholar Michele Deitch describes as “an anomaly on the world stage.” And courts are not well suited for this job: they’re reactive and narrowly focused on specific complaints, they move slowly, and they’re expensive. Perhaps most importantly, incarcerated people are routinely blocked from using them thanks to laws like the Prison Litigation Reform Act. So, what makes for effective oversight? Which states have oversight bodies and which don’t? And what are the differences between the various models?

Fortunately, PrisonOversight.org is working to answer questions like these, providing critical resources to a movement for more oversight that, according to a recent survey from Families Against Mandatory Minimums, 82% of Americans support. Here, we preview some of the data they’ve collected and encourage you to explore the site and support this essential project.

The state of prison oversight

PrisonOversight.org is a project of the National Resource Center for Correctional Oversight (NRCCO), which supports advocates, policymakers, and government officials in developing and strengthening oversight. Michele Deitch co-runs NRCCO alongside Associate Director Alycia Welch — another leading expert in correctional oversight.

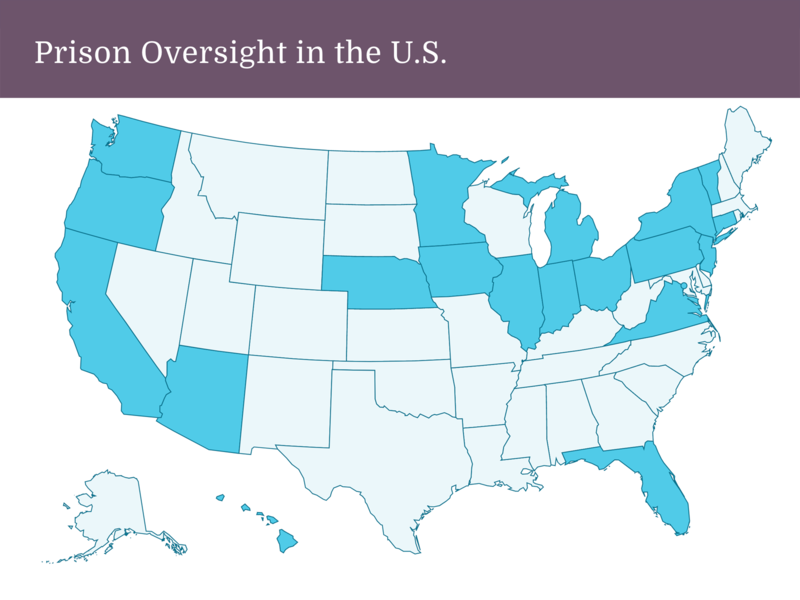

One of the website’s most significant contributions to the movement is a helpful inventory of state-level oversight. According to their map, 19 states and the District of Columbia have an external, independent prison oversight body, while 31 states do not.

Each state has a detailed profile that includes the most recent annual budget appropriation for oversight, staff size, structure, and more. According to their data, there is wide variation among the small group of states that have oversight bodies:

- Oversight budgets range from $200,000 (Nebraska) to $42 million (California) annually.

- Full and part-time staffing ranges from one person (Oregon’s lone ombudsman) to 211 (California); half have ten or fewer staff.

- While some are quite old,1 most oversight bodies that exist today were established or re-established after the 1970s; nine have only been around since 2000. Five states have spun up oversight agencies since 2020.

- Only three of the 20 oversight bodies were non-governmental organizations.

- Four of the oversight bodies are so new that we lack basic information about them, such as their expected staff size, budget, and activities.

NRCCO is developing similar resources about jails and court-ordered oversight bodies that they will publish in the future.

What does effective oversight look like?

In her work analyzing corrections oversight internationally and in the U.S., Deitch notes that “The sheer geographical size of the United States, the enormous number of people incarcerated, and the federalist structure of our correctional system make a single national system of independent oversight impractical.” The best practice, she argues, would be for both state prisons and county jails to receive state-level oversight. She also highlights some helpful attributes of strong and effective oversight bodies. They must:

- Be independent of and external to the correctional agency;

- Have a mandate to conduct regular, routine inspections;

- Have unfettered, “golden key” access to the facilities, incarcerated persons, staff, and records, including the ability to conduct unannounced inspections;

- Be adequately resourced, with appropriately trained staff;

- Have a duty to report publicly their findings and recommendations;

- Use an array of methods of gathering information and evaluating the treatment of incarcerated people;

- Be required to cooperate fully in the inspection process and to respond promptly and publicly to the monitoring body’s findings and recommendations; and

- Focus monitoring duties on the treatment of incarcerated people and any risks the institution presents to their health, safety, and civil rights.

These lessons are clear in PrisonOversight.org’s design. The website’s helpful Oversight 101 section delves into the basics behind some of these attributes, noting, for example, that layered approaches to oversight are best. One section examines the limitations of leaving everything to the courts or placing too much faith in accreditation alone. There’s information on challenges in practicing oversight, such as insufficient staffing or insulation from political pressure. Helpful resources like model prison oversight legislation and links to recent legislation can help advocates and policymakers keep up with oversight experiments around the country. The Developments section tracks job opportunities in the field, conferences, and news reports.

No more taking impunity in corrections for granted

For hundreds of years in the U.S., incarcerated people have been abandoned to fight for their dignity and safety at the hands of officials who have little interest in or incentive to oblige. They are shunned from society through criminalization and incarceration and then plunged into opaque institutions designed to neglect, if not actively reject, their best interests. Their disappearance from public view perpetuates their abuse while law enforcement and correctional authorities enjoy complete control over what information makes it outside. Independent, external oversight can help shift this balance of power: by collecting and publicizing data on the conditions facing people in these institutions, oversight bodies can help incarcerated people overcome the brutal retaliation they face for speaking out. While enforcement powers vary across these oversight experiments, we all benefit from their ability to provide a meaningful counter to the opportunistic myth-making and rationalizations upon which mass incarceration has thrived.

Resources like PrisonOversight.org are helping to build the momentum for accountability that is long overdue. This project gives advocates helpful information to inform their strategies and public education efforts. It’s also an excellent resource for reporters to learn about what does or does not exist in their state, how oversight bodies work, who serves on them, and what they do and don’t publish. And researchers and policymakers benefit from the collection of state-by-state practices, with a level of detail that allows us to both see the big picture and experiment with different models.

We are grateful that a project like PrisonOversight.org has arrived on the scene. We highly recommend you check out their resources and incorporate the wisdom and recommendations it contains into your campaigns.

Footnotes

- Some oversight bodies, like the Correctional Association of New York and the Pennsylvania Prison Society, were established in the 1800s.

↩

This article was originally published by Prison Policy Initiative as “Research spotlight: PrisonOversight.org equips the fight for accountability in jails and prisons,” authored by Brian Nam-Sonenstein