Este artículo fue publicado originalmente por Prison Policy Initiative como “Los candidatos a cargos públicos utilizan la cárcel y la prisión como soluciones políticas de “talla única”. Aquí se explica cómo contrarrestarlas”, escrito por Wanda Bertram.

Ya sea en el escenario del debate presidencial o en las carreras para gobernador, legislaturas estatales o consejos municipales, los candidatos a cargos electos están recurriendo a una vieja táctica: hacer afirmaciones falsas de que “el crimen ha aumentado” y presentar más tiempo en prisión como soluciones a los problemas sociales. No solo las afirmaciones de un mayor crimen son demostrablemente falsas; el encarcelamiento nunca es la solución simple que parece ser. Las cárceles y prisiones, incluso cuando se reconstruyen y Calificado como “humanitario” — siguen siendo lugares de castigo, y la inversión en ellos sistemáticamente no logra producir comunidades más seguras ni, obviamente, desmantelar el encarcelamiento masivo.

Los argumentos a favor de más cárceles pueden parecer interminables, pero si los candidatos que hacen campaña para un cargo en su comunidad o estado promueven la idea de que más encarcelamientos son una buena idea (o incluso un mal necesario), lo tenemos cubierto. A continuación, presentamos datos que puede utilizar para oponerse a las afirmaciones falsas sobre lo que se puede lograr con la criminalización, ya sea en relación con la falta de vivienda, la crisis del fentanilo o la seguridad pública en general.

HECHO 1: Encarcelar a personas que consumen drogas es contraproducente.

En medio de una crisis de sobredosis, muchos legisladores y candidatos a cargos electos están haciendo campaña Se trata de una reforma que implica la detención de más personas por consumo de drogas, especialmente en espacios públicos. Estas reformas son una flagrante reformulación de las políticas de la “guerra contra las drogas” y un paso atrás en materia de salud pública.

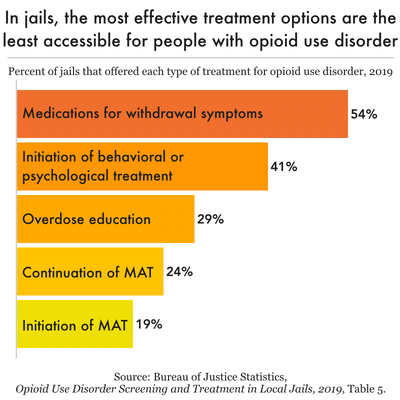

Es importante destacar que, aunque presionan para que la policía intervenga como un medio para que los consumidores de drogas inicien el tratamiento, los funcionarios públicos a menudo ignoran que, para empezar, puede que no haya suficientes recursos para el tratamiento del consumo de sustancias en la comunidad. Oregón, que posesión de drogas recriminalizada A principios de este año, sólo tiene 50% de los recursos de tratamiento que el estado necesita. Una vez en prisión, las personas que han consumido drogas de forma nociva no tienen muchas posibilidades de recibir tratamiento, y mucho menos atención genuina. Reunión informativa a principios de este año, demostramos que menos de una quinta parte de todas las cárceles del condado en los EE. UU. inician un tratamiento asistido con medicamentos para el trastorno por consumo de sustancias, y apenas la mitad de todas las cárceles del condado Incluso proporcionan medicación para la abstinencia.

Además, estar en prisión puede hacer que el consumo de sustancias sea peligroso o incluso mortal. Los datos de 2018 muestran que las muertes relacionadas con las drogas y el alcohol en las cárceles han aumentado. casi cuatro veces Desde el año 2000, la media de tiempo que se pasa en prisión antes de morir por intoxicación es de tan solo un día. Si bien arrestar a las personas que consumen drogas en público puede ayudar a que algunas de ellas inicien un tratamiento, para otras hace que su adicción sea más mortal, lo que no es una política de salud pública sensata.

HECHO 2: Más viviendas, no la criminalización, es la respuesta a la crisis de las personas sin hogar.

Muchos líderes locales y estatales están comenzando a aplicar con dureza sus leyes contra los campamentos a raíz del caso de la Corte Suprema Paso de Grants contra Johnson, que sostuvo que los estados tienen el derecho de limpiar los campamentos de personas sin hogar incluso cuando no hay camas disponibles en los refugios. Pero, contrariamente a lo que dicen muchos de estos legisladores, las respuestas punitivas a la crisis de las personas sin hogar no son "sentido común."

Muchas personas sin hogar ya tienen antecedentes penales, lo que puede hacer que sea extremadamente difícil encontrar un lugar donde vivir. Ya hemos hablado antes de cómo autoridades de vivienda pública Tienen —y utilizan— amplia discreción para negar alojamiento a personas con antecedentes o incluso solo antecedentes de arresto. Para estas personas, la falta de vivienda puede ser el resultado de encuentros pasados con la policía. Para otras, un roce con la policía o una temporada en la cárcel podría hacer que encontrar una vivienda en el futuro sea menos probable. En nuestro informe de 2018 No hay ningún lugar a donde ir, descubrimos que las personas que habían estado en prisión tenían más probabilidades de quedarse sin hogar dependiendo de cuántas veces habían estado encarceladas: cada encierro aumentaba la probabilidad de terminar en la calle sin perspectivas de vivienda.

Como Otros han señalado, Las crecientes tasas de personas sin hogar en Estados Unidos son el resultado de una auténtica crisis de vivienda. Las personas que han estado encarceladas y las que corren el riesgo de ser encarceladas son las más necesitadas. Pero hay respuestas políticas que funcionan. Informe de 2023, Descubrimos que los programas de vivienda de apoyo a largo plazo que no son Las políticas basadas en que las personas estén sobrias o acepten el tratamiento tienen tasas increíbles de éxito en mantener a las personas alojadas y fuera de la cárcel.

HECHO 3: La solución a las cárceles superpobladas e inhumanas es la reforma preventiva y la atención sanitaria comunitaria.

En los condados y ciudades donde las cárceles están abarrotadas o enfrentan una larga lista de costos de mantenimiento y reparación, los funcionarios locales que se presenten a las elecciones este otoño probablemente se verán presionados a votar sobre la construcción de nuevas cárceles, a menudo más grandes. (Y en algunos condados, las propias medidas de construcción de cárceles están en la boleta electoral).

Los funcionarios electos a nivel de condado y ciudad a menudo afirman que "no tienen otra opción" que ampliar o reemplazar sus cárceles (por ejemplo, recientemente, en Cleveland y Sacramento). Pero estos proyectos enormemente costosos a menudo no producen los resultados que los gobiernos locales desean. En los condados con cárceles superpobladas, se supone que construir una cárcel más grande facilitará la supervisión y el cuidado de la población carcelaria. Pero con demasiada frecuencia, estos proyectos conducen a Más encarcelamientos —Y la nueva cárcel también queda superpoblada.

De hecho, los condados hacer Los presos tienen la posibilidad de elegir cómo abordar los problemas en sus cárceles. Los tribunales locales y los alguaciles del condado pueden trabajar juntos para reducir la población carcelaria mediante la reforma de la prisión preventiva, algo que hemos demostrado que se puede lograr. sin perjuicio de la seguridad pública. Y en los muchos, muchos condados donde La mayoría de las personas en prisión tienen un trastorno por consumo de sustancias, ampliar las opciones de atención médica comunitaria es una forma más económica y más eficaz de abordar la adicción. también reduce el número de personas tras las rejas.

HECHO 4: Las reformas de “Verdad en las Sentencias” convierten las cárceles en hogares de ancianos superpoblados con poco o ningún beneficio para la seguridad pública.

A principios de este año, el gobernador de Luisiana, Jeff Landry, y su legislatura, que es “duro con el crimen”, impulsaron “La verdad en la sentencia” Leyes que eliminaron la libertad condicional en las prisiones del estado y prohibieron a las personas obtener tiempo para descontar sus sentencias. Sus reformas regresivas son parte de una reciente ola de legislación, Principalmente en el sur. Sin embargo, proyectos de ley similares al de Landry han llegado a estados como Colorado y Iowa también.

Pedir que más personas pasen décadas y probablemente mueran en prisión es una estrategia de campaña popular. Pero la realidad de la verdad en las sentencias es brutal y contraproducente. El sistema penitenciario de Estados Unidos ya está volverse geriátrico A medida que las personas sentenciadas en los años 70, 80 y 90 envejecen, se elimina la libertad condicional y otros mecanismos de liberación anticipada (como juerga, que Landry llamó despectivamente “Un trofeo de participación para la cárcel”) acelerará esa tendencia. También aumentará la población carcelaria, como en Luisiana, donde el Instituto del Crimen y la Justicia Proyectos que las reformas regresivas duplicarán la población carcelaria estatal. Y como consecuencia tanto del hacinamiento como del “encanecimiento” de las prisiones, más personas en prisión se enfermarán, lo que conducirá al tipo de situaciones médicas espantosas por lo que son conocidas las cárceles.

Teniendo en cuenta estos enormes inconvenientes, puede resultar sorprendente que obligar a las personas a cumplir más tiempo en prisión no mejore, de hecho, la seguridad pública. Si los candidatos a legislador estatal o gobernador proponen estas reformas “duras” en su estado, recuérdeles que “la verdad en las sentencias” reduce los incentivos para que las personas encarceladas completen programas que puedan ayudarlos a ellos y a sus comunidades. Y el Investigación del Instituto Vera También puede ser útil tener a mano información sobre la ineficacia de las penas de prisión más largas.

HECHO 5: La delincuencia ha disminuido, no aumentado.

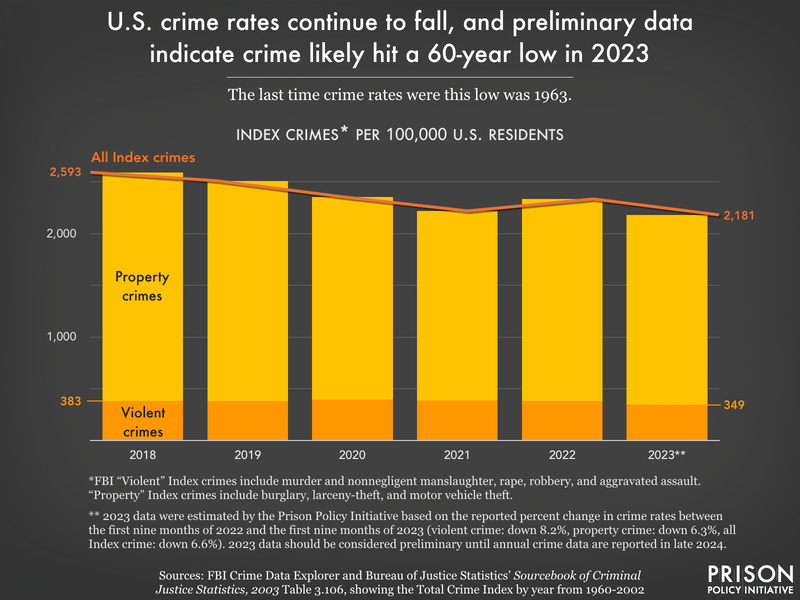

La delincuencia no está aumentando, a pesar de que los candidatos a cargos electivos, incluido Donald Trump y otros de los dos partidos principales en todas las áreas de la boleta, pretenden lo contrario. Las afirmaciones sobre el aumento de la delincuencia pueden ser muy persuasivas: en octubre de 2023, 77% de los estadounidenses encuestados Se creía que había más delitos en Estados Unidos que el año anterior, pero, como muestran los datos antiguos y nuevos, esto simplemente no es cierto. Nuevos datos de la Oficina de Estadísticas de Justicia Los datos sobre victimización criminal en 2023 muestran que los delitos de casi todos los tipos disminuyeron con respecto a 2022, y muchos tipos de delitos violentos fueron iguales o inferiores a sus tasas reportadas en 2019.

Es cierto que la delincuencia puede fluctuar rápidamente en períodos cortos de tiempo, pero los funcionarios electos pasan varios años en el cargo y deberían hacer campaña sobre su capacidad para proteger la seguridad pública a largo plazo. ¿Qué dicen entonces los datos sobre la delincuencia a largo plazo? En resumen: En 2023, la delincuencia alcanzó su nivel más bajo en 60 años. Los candidatos a un cargo público no deberían centrar sus campañas en aumentos de la delincuencia que, en esta perspectiva a largo plazo, son momentáneos y bastante modestos.

Poner fin a la desinformación sobre el crimen y la seguridad no sólo implica poner fin a las afirmaciones falsas sobre el crimen. Los legisladores deberían adoptar una visión amplia de la seguridad pública y abordar las tendencias reales y perjudiciales, como la escasez de viviendas, la desigualdad económica y los problemas de salud pública. Las personas que elegimos para gobernar nuestras comunidades tienen una gran cantidad de información sobre los diversos factores que impulsan el crimen y la seguridad, y deberían utilizarla.

Conclusión

Los legisladores que promueven la verdad en las sentencias, cárceles más grandes y otras políticas que amplían el sistema legal penal tienden a afirmar que no hay alternativa a estos métodos para hacer que las comunidades sean más seguras. Pero las alternativas que han demostrado funcionar La vivienda primero, reducción de daños, Libertad condicional ampliada y “buena conducta” — a menudo son ignorados por estos mismos legisladores, o no se les da la oportunidad de atender a más de un puñado de personas en un programa piloto. Mientras tanto, el sistema legal penal sigue consumiendo cientos de miles de millones de dólares, incluso cuando las cárceles parecen convertirse en Cada vez más inhumano.

Nunca es demasiado tarde para presionar a los funcionarios electos —y a los candidatos que se postulan para reemplazarlos— para que prueben estrategias de seguridad pública que se centren en la atención, no en las jaulas. Más o menos todos los funcionarios electos tiene un papel que desempeñar en el desmantelamiento del encarcelamiento masivo, y el movimiento para ese cambio debe comenzar con presión desde abajo.

Este artículo fue publicado originalmente por Prison Policy Initiative como “Los candidatos a cargos públicos utilizan la cárcel y la prisión como soluciones políticas de “talla única”. Aquí se explica cómo contrarrestarlas”, escrito por Wanda Bertram